The Story of MacWrite

The rise and fall of the Macintosh's original word processor

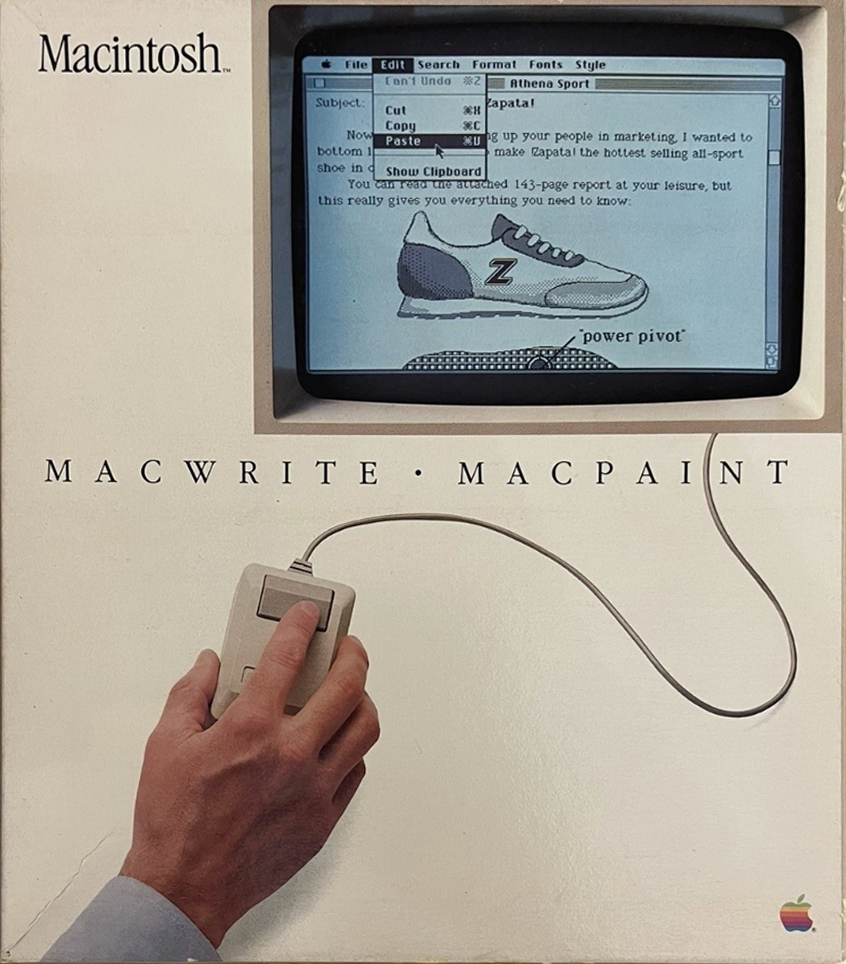

When the Macintosh was released in 1984, it did not exactly launch with a rich collection of software available. This was not necessarily a fault, the IBM PC hadn’t launched with many applications either when it hit the market in 1981.1

However the Macintosh did need at least some basic applications available at launch, and one of the most significant needs was for a word processor of some sort. Word processing was a key task for personal computers in the early 80s…not like it isn’t still a key task, however it’s easy to underestimate just how important word processing was when the Macintosh launched. This was an era when most people were still using typewriters, and expensive word processors.

Entire software (and usually long-since vanished) businesses were built off of a good word processor (for example, LazyWriter for the TRS-80, EasyWriter for the Apple II, etc), as customers eagerly traded in their battered typewriters for the convenience and speed of non-linear text editing.

With its crisp bit-mapped screen that gave it the ability to display fonts (as opposed to the IBM PC’s character based displays)2, the Macintosh was a natural fit for true WYSIWYG word processing, something that Steve Jobs was very well aware of.

Enter Randy Wigginton, a brilliant, self-taught programmer who as a high-schooler had handled the work needed to adapt3 Microsoft’s BASIC4 to work on the Apple II. Wigginton was one of the first few programmers working on the Macintosh project, but he was unhappy and getting burned out.

Although he had started with the best of feelings, the constant, unrelenting pressure and browbeating from Steve Jobs had worn him down and he was tired of dealing with it on a day-to-day basis. Hence, after Apple’s 1981 annual meeting, he formally resigned from Apple.

Randy’s resignation letter created a major problem for the Macintosh project in general and Steve Jobs in particular (or possibly the other way around), as his next major project was supposed to be developing MacWriter. And as of the end of 1981, Steve was still committed to the increasingly-hilariously-off Macintosh release date of October 1982.

With that date less than a year away, Jobs needed a word processor, and he needed it in record time. But Wigginton was uninterested. So Jobs considered his options, realistically he had a grand total of two. Either contract with an outside developer to create MacWrite, or get someone else from within Apple to do it.

Apparently Jobs did consider poaching away the developer working on the Lisa’s word processor, LisaWrite. However, “the word from Atkinson and Hertzfeld was that LisaWrite was a mess—slow and with convoluted code that was a nightmare to debug.”5

Atkinson (creator of QuickDraw, MacPaint, and HyperCard among other feats) and Hertzfeld (one of the dominant software developers behind the creation of the original MacOS and developer of the brilliant Switcher system extension that gave the single-tasking MacOS a form of multitasking among other feats) were two of the very few people that Jobs deeply respected. The fact that they clearly didn’t care for LisaWrite was enough for Jobs to abandon any thought of poaching its developer for MacWrite.

However, no outside developers would commit to having MacWrite ready to go by Jobs’ deadline of October 1982. So Jobs decided that the only thing to do was to get Wigginton to agree to develop MacWrite, just as an outside developer.

Given the fact that Wigginton had left Apple because of Steve Jobs, he was initially unreceptive to Jobs’ pitch to him. He finally said he would do it for a cool million dollars, thinking that Jobs would balk at that figure and go away. However if he said yes, “I figured that for $1 million I could put up even with Steve,” but Wigginton didn’t really expect Jobs to go for it.

Jobs initially demurred, but after mulling things over for a bit, he came back to Wigginton and offered him a compromise deal. If Wigginton developed MacWrite and had it ready to go by the Macintosh’s release date, Apple would pay him a royalty of two dollars per Macintosh sold all the way up to one million dollars and would pay Wigginton a 500 thousand dollar advance.

The contract also called for Wigginton to do an upgraded version of MacWrite down the road, and gave Apple the rights to MacWrite. Wigginton had no problem with this, since Apple promised him that MacWrite would never be sold, but rather would be bundled together with other applications that were included with every Macintosh purchase.

With both parties in agreement, the contract was signed just before Christmas of 1981, and Wigginton immediately buckled down and got to work. That deadline was going to be very tight…although of course that was only going to be the case if the Macintosh actually came out in October of 1982.

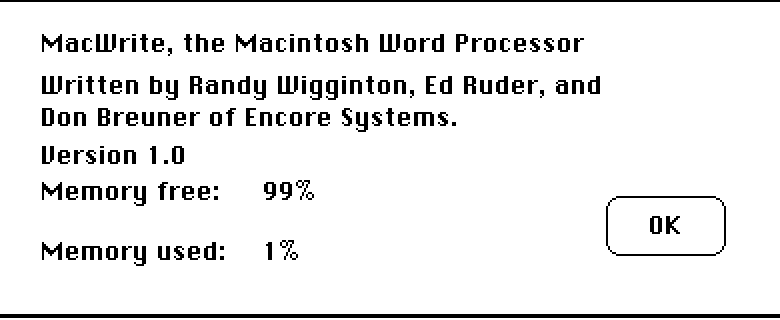

Now, Wigginton wasn’t the sole developer working on MacWrite, rather, the contract was between Apple and Wigginton’s small software company, Encore Systems. MacWrite’s development would be handled by Wigginton himself of course, plus Ed Ruder and Don Breuner.6

Wigginton had founded Encore Systems right after leaving Apple, and was apparently almost immediately joined by Ruder and Breuner, who had all been in high school with Wigginton.

Together, these three men would develop one of the first GUI based WYSIWYG word processors for a personal computer. It is important to set the proper context though, as first Bravo and then Gypsy had been developed at Xerox PARC almost a decade prior, both of which were pioneering graphical word processors that ran on the Alto personal computer.7

However, consumer desktop computers were a far cry from the lavish hardware available at something like PARC, and for many people MacWrite would be the very first GUI based word processor that they would ever see and use.

And MacWrite would do all of this in Motorola 68k assembler, with the Macintosh’s tight RAM constraints forcing them to write code as tightly as possible in order to leave as much RAM available to hold the actual document as possible. Even then, the first version of MacWrite was going to be very limited in how much text it could hold…just ten pages (give-or-take depending on spacing, font size, and a few other things).

But that’s getting ahead of the story.

In February of 1982 Steve Jobs took the Macintosh team out for the first team retreat. Over the course of two days at a seaside resort in Pajaro Dunes, meetings were held as various Macintosh groups presented their project statuses, their end goals, and what they had accomplished so far.

Steve Jobs also announced that the Macintosh’s launch date had been pushed back to May 1983, handing out t-shirts with “May 16, 1983” printed on the back. Wigginton, included because of MacWrite’s importance even though he was no longer an Apple employee, also showed the first version of MacWrite.

This early version was extremely rough, as development was still in the early stages, but it was far enough long for feedback to be given. Something that was immediately evident was that the Macintosh’s screen was too low of resolution for MacWrite to show 80 columns of text.8

The current Macintosh specifications called for a screen 384 dots across, which was a not-inconsiderable increase from Jeff Raskin’s original specifications for a 256 dot wide resolution. But this still wasn’t enough to get MacWrite to display 80 columns of text, they really needed 512 dots of horizontal resolution.

Why was this important? Because the Macintosh team was determined to allow for true What You See Is What You Get word processing (usually abbreviated WYSIWYG), and the first and most obvious part of that was for the screen to display columns of text that broke in exactly the same place they would when printed on a standard 8.5x11 sheet of paper.

Consider the world of personal computing in 1983. The IBM PC was natively capable of 80 columns, but the Apple II was only capable of 40 columns, as was the Commodore 64. The VIC-20 was even more limited, displaying a mere 22 columns9, while the TRS-80 Model III could do 64 columns.

There were any number of solutions to give these other computer 80 column displays, some using hardware expansion cards and others using software tricks such as shrinking the various characters horizontally in order to cram more onto the screen. This last option tended to result in very pinched looking text that was a bit of an eye strain to read, especially on a fuzzy TV screen.

The goal for MacWrite was to give the Macintosh a word processor that was truly WYSIWYG, and that started with making 80 columns fit on the crisp black and white display. As a side note, the Macintosh’s screen may be quite low resolution by today’s standards, but it was essentially a 1984 Retina display, a screen so crisp and sharp that when paired with Susan Kare’s brilliant work on the MacOS it caught people’s attention all on its own.

And so the Macintosh was redesigned, with Jobs exploring two hardware options for increasing the display resolution. The first one involved a man named Martin Haeberli, a chip designer that Jobs lured away from Xerox with the promise of a bonus totaling tens of thousands of dollars (forty percent paid in advance) for successfully delivering a custom chip that would increase the Macintosh’s screen resolution (plus a bunch of other things that Jobs wanted done in order to reduce the Macintosh’s chip count).

Assisted by Burrell Smith, Haeberli struggled to design an incredibly complex chip that would not only increase the Macintosh’s resolution Jobs’ desired 512x384, but also replace somewhere around 20 chips on the current Macintosh board. The project was insanely ambitious, Jobs kept pushing for more and features to be incorporated into the new chip, and he wanted it all done in less than four months.10

As Haeberli fought to get a working chip out inside of the insanely unrealistic deadline, and with Jobs ratcheting up the pressure, Burrell decided to try to approach the problem from a different direction, using PALs (Programmable Array Logic chips, not the old European television video standard)

This second approach was solely focused on upping the Macintosh’s screen resolution to the desired 512x384 pixels, and in only about a month of work Burrell managed to make it work. Burrell was a brilliant PAL designer, and the initial hardware design for the Macintosh had been heavily reliant on PAL chips.

Haeberli had also miraculously managed to get a working version of his chip design, however the first batch of prototype chips ran at only 60 percent of the needed speed. Given the vagaries of chip design, especially with the comparatively primitive tools available in 1982, Haeberli’s accomplishment was substantial. Plus using it could noticeably drive down the cost of building the Macintosh, since it replaced so many chips.

So by Labor Day of 1982, Jobs had two competing choices before him to boost the Macintosh’s resolution. One of those options, Haeberli’s, could do a lot more than just raise the Macintosh’s resolution, but needed an unknown amount of revision and refinement to actually make it production worthy. The other option, Burrell Smith’s, simply increased the Macintosh’s resolution to the desired 512x384 and that was all it did.

Undoubtedly Haeberli would have been able to revise the chips and reach the needed speed…if Jobs had given him the needed time. However with that claimed Macintosh release date of May 1983 drawing closer and closer, and a scheduled Macintosh design freeze set for January of 1983…Jobs decided to go with Burrell’s PAL design instead of taking a gamble on Haeberli’s chip.

In spite of his disappointment (probably putting it lightly considering all the work he had put in) Haeberli continued to work on other areas of the Macintosh, including its memory manager and helped write MacTerminal, the first terminal application released for the Macintosh (this was not a terminal in the command prompt sense, it was a terminal used for dialing into BBS services or other early networking/Internet services). He also was one of the Macintosh team members to have his name on the original Macintosh 128k die.11

Meanwhile, work on MacWrite continued, now targeting an 80 column display. However Jobs still was meddling with it, even though Wigginton of course no longer worked for him. When Wigginton and his team added cursor key support to MacWrite, enabling the user to move the cursor around the document without needing to utilize the mouse—Jobs ordered them to take it out.

Wigginton said he told Steve “What difference would it make? Why not just add that little feature to make it easier for secretaries? But no. We couldn’t have them. ‘We have to face the issue—make people use the mouse. It’s better for them,’ was what he told me.”12

And so Wigginton continued developing MacWrite, polishing it up to a high degree and making sure it was a smooth, intuitive user experience. His hard work paid off, which was a good thing since (among other reasons), the Macintosh was in dire need of launch applications.