The Macintosh and Excel

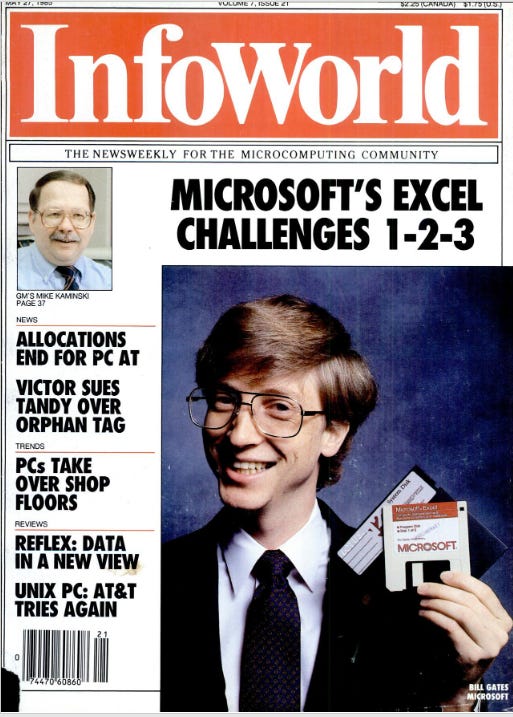

Bill Gates and Microsoft create the earliest "Killer app" for the Macintosh

Apple and Microsoft have a history of being the Hatfields and McCoys of the computing world, two rivals endlessly dueling over the personal computer market, with each side having legions of supporters engaging in holy war with one another.

Yet this obscures the fact that Apple and Microsoft have been extremely useful to one another over the last four decades, and each one of them played a significant role in the other’s success. Sure they fought each other in a series of bitter court battles, but Microsoft also gave a much needed cash infusion to Apple in 1997, when they invested 150 million dollars1 in Apple stock at a time when Apple desperately needed the cash to help keep things running while Steve Jobs and his team worked to turn Apple around from its collapse.

Obviously Gates didn’t do this sort of thing out of charity, it made good business sense for Microsoft, who was still fighting a court battle at the time, to have a rival that it could point to as proof that it wasn’t a monopoly.

Microsoft was also a key developer for the Macintosh in the 1980s, one of the most significant ones in fact. And it was on the Macintosh that the spreadsheet titan Microsoft Excel first made its appearance, with version 1.0 being released on September 30th, 1985, several months before the first version of Windows made its much ballyhooed appearance.

Excel was also, oddly enough, not available for MS-DOS, the operating system that Microsoft controlled and which ran on the majority of the personal computers of the mid 1980s. To the contrary, Excel was exclusive to the Macintosh for several years. And the question of why boils down to really one name…Lotus 1-2-3, the reigning champion of the PC spreadsheet market.

In 1985, Lotus 1-2-3 had finished demolishing VisiCalc’s market share. VisiCalc was the world’s first spreadsheet for a personal computer, however in 1985 VisiCalc creator Personal Software and their publisher VisiCorp were locked in a nasty court battle that ensured that both companies would collapse (Infoworld ran a half-serious, half somber ode to it in the same May 27, 1985 issue that introduced Excel2).

And thus Lotus 1-2-3 quickly rose to prominence with its most serious competitor distracted, and then began demolishing the other spreadsheet names of the era, such as SuperCalc. Lotus 1-2-3’s success also ensured that Microsoft’s own existing MS-DOS spreadsheet, Multiplan, was unable to gain significant market share in America, although in fairness it did do quite well in some foreign markets, most significantly Europe.

Seeing what was going on, in 1983 Gates had convened an internal three day conference at the Red Lion Hotel in Bellevue Washington, to work out a new spreadsheet strategy. The Microsoft brain trust assembled here was formidable, including Gates himself, Jeff Raikes and his assistant Jabe Blumenthal, Charles Simonyi, and a few programmers including Doug Klunder, Jeff Harbers, and Bob Matthews. What came out of this meeting was a list of specifications for a brand new spreadsheet application that would be the “ideal spreadsheet” for the MS-DOS market.

Gates then selected one of the original Multiplan developers, Doug Klunder, to head up the new spreadsheet, temporarily given the name of Odyssey. Klunder’s best friend and fellow Microsoft employee, Jabe Blumenthal, gave it this name because the new spreadsheet was not only aiming to be a “Lotus-eater” but also to express Blumenthal’s doubts about the overly optimistic development schedule.

Ulysses had taken seven years to get home after all, and while Blumenthal did not expect Odyssey to take that long, he did think Microsoft’s goal of having Odyssey done in six months in order to be released in summer of 1984…was a tad optimistic.

Blumenthal himself would function as essentially Odyssey’s program manager, although that title did not really exist yet at Microsoft. He would be in charge of Odyssey's specifications and feature implementation, looking at it from more of a marketing perspective (appropriate since Blumenthal was a marketing manager) than a programmer. His previous experience in marketing Multiplan would be useful in shaping Odyssey’s direction, as he was very familiar with the features of VisiCalc, SuperCalc, 1-2-3, and of course Multiplan.

The main driving goal of Odyssey was, as Klunder put it, to “do everything 1-2-3 does and do it better. Plus intelligent recalc.3” Intelligent recalc refers to only recalculating spreadsheet cells whose values were affected by a change in a given cell. In Lotus 1-2-3 any change in a spreadsheet forced the computer to recalculate the entire thing. And while that task is so trivial today as to be a completely pointless feature, on a 4.77 mhz 8088 it induced noticeable delays in performance.

Yes it's true, there was a time when Microsoft actually had a goal of making a piece of software run faster than the competition. But since Chrome didn’t always require a fully specced out Mac Pro with 2 TB of RAM in order to open more than four tabs, companies and priorities do change over time.

Klunder was not a man to give way to anybody, and was fully willing to go toe-to-toe with Gates if needed, in order to make Odyssey happen his way. An early example of this came when Klunder wanted Odyssey to use a unique language for its macros, and Gates wanted that language to be BASIC.

The two clashed over it, but Klunder’s view prevailed in the end. As he put it “Bill will be very argumentative and call you on stuff. But you can also tell him he’s full of sh– and get him to back down. Most people are too scared to do that, but I think actually what he respects most is if they call him on his random claims.4”

Although Klunder had been promised the assistance of one of Microsoft's programmers to work with him, he instead got a fresh college graduate. This was possibly due to Windows’ increasing tendency to vacuum up Microsoft's top programmers, but fortunately the programmer was extremely good.

Microsoft in the 1980s only hired programmers who were the absolute best, even extending to hiring ones they didn’t necessarily need at the moment, just to lock down top talent.

Although originally planned for MS-DOS, Gates briefly decided that Odyssey should instead target the as-yet-unreleased Windows which was still in the middle of its turbulent development. This went over about as well as you might expect with Klunder, who confronted Gates, who claimed he had just been more-or-less thinking out loud and hadn’t actually decided yet.

Klunder then went into an extremely intense meeting with Paul Allen, with Klunder saying he “basically screamed” at Allen that Odyssey was already a mouse based application and didn’t need Windows. Although Odyssey for Windows was dropped after this meeting, its target platform of MS-DOS was also dropped in favor of the Odyssey being solely for the Macintosh.

Klunder was not happy about this, feeling that Microsoft was running from the 1-2-3 juggernaut without even trying to fight, which would effectively result in conceding the entire MS-DOS spreadsheet market to Lotus. But Gates had a strategic reason for making this massive shift in focus.

In February of 1984, he had learned that Lotus was planning a full scale assault on the Macintosh spreadsheet market with a new, specially designed application called Jazz. Jazz was not only for the Macintosh, it was also being developed for the MS-DOS based market that Lotus 1-2-3 already ruled. Odyssey was going to run straight into some fierce competition right from the start. And it wouldn’t be a straight spreadsheet-to-spreadsheet joust.

Jazz was more than a spreadsheet, it was an integrated product that would contain not only a spreadsheet but also applications for “database, graphics, word processing, and communications.5” These types of integrated products were all the rage in the early 1980s, with a lot of buzz behind them. In a world where applications were a lot closer to an operating system than they are today, and running multiple programs simultaneously was difficult-to-impossible to do, integrated programs promised to give the user the ability to handle most or all of their standard productivity tasks from inside a single application.

Gates recognized that since graphical applications were the future, he could not afford to let Lotus grab control of the graphical spreadsheet market on the Macintosh. The spreadsheet market on MS-DOS was already dominated by Lotus, with the company raking in more money from Lotus 1-2-3 alone than Microsoft made from every single one of their products combined6. The Mac, which had only just been released in early 1984, was still struggling for software and lacked a good spreadsheet as Lotus 1-2-3 was not currently planned to be ported to it.

The decision to throw away the existing MS-DOS development of Odyssey and start from scratch targeting the Macintosh, was made on March 5, 1984, a scant two months after the Macintosh was officially launched7. Granted, Microsoft had already released Multiplan for the Macintosh in 1984, but it was clearly a stop-gap solution as it was not really Macintosh focused and had already lost to 1-2-3 on the desktop.

Gates gambled that if he could jump in with a good spreadsheet that worked well with the Macintosh’s graphical user interface, he could corner the spreadsheet market on the Mac, freeze out Lotus’s Jazz, and then use that as a beachhead to expand Odyssey to other graphical operating systems in due time.

Gates also knew that an upgraded Macintosh, the Mac 512k was planned for release later that year and with four times the RAM of the original Macintosh, paired with the same powerful Motorola 68000, it would have the ability to support a very powerful spreadsheet, exactly the kind of spreadsheet he intended Odyssey to be.

Gates also decided to stick to developing Odyssey as a dedicated spreadsheet, not an integrated program like Jazz. Odyssey would be aimed solely at advanced users, with a powerful feature set and interface designed to take full advantage of the Mac and its new GUI.

In March of 1984, Jerry Ruttenbur, a former marketing and sales executive for M&M Mars, was brought on as vice-president of Microsoft's retail sales division. One of Ruttenbur’s earliest actions was helping to come up with a new name for Odyssey, which was renamed to Excel. Other names that were considered were8 “NumberBody”, “Plan 3”, “Champagne”, “Lever”, and my personal favorite, “Mister Spreadsheet”.

However the shift of focus to Macintosh only, with the associated throwing away of all of the labor that Klunder had been putting into developing it for MS-DOS, was the final straw for Klunder, who said “Bill just screwed up from a human management point of view. I was killing myself with Excel.9”

Klunder was also deeply upset because he had a lot of stock options tied to successfully completing Excel by the original due date, and throwing away all the PC code and moving to a Macintosh only release would undoubtedly push the project completion date back quite a bit.

Programming a Macintosh at this point was also quite difficult as many of the tools needed were either non-existent or very early in development. Switching Excel from targeting MS-DOS to targeting the Macintosh required learning a completely different way of developing.

As a matter of fact, until 1985 Macinotsh development couldn’t even be done on the Macintosh itself, the developer had to aquire an expensive Apple Lisa, do the development on that (typically in Pascal), and then use a utility called the “MacCom Lisa-to-Macintosh” to transfer the program to a Macintosh for testing.10

Klunder wound up deciding to just resign entirely, but when he told Ballmer this it touched off a heated argument with both men shouting. At 8 PM that same day, Gates personally brought Klunder in for an intense meeting to try to persuade him to stay, and this meeting lasted until 3 AM.

Klunder finally agreed to stay for another nine months, but only on the condition that he only work forty hours a week and that Microsoft not try to pressure him into staying once the nine months were up. Klunder then worked with Charles Simonyi to create a new thirty page project specification for Excel.

Blumenthal also worked on Excel’s specifications from an end-user point of view, reworking the existing MS-DOS specifications to align with the Macintosh’s user interface and conventions. Mike Slade, who had been brought on board as Excel’s marketing product manager (although I’m not sure if “product manager” was the term used) aided him.

In November of 1984, Jazz was officially announced by Lotus, who were pulling out all the stops to promote it. Apple’s John Sculley spoke at the launch event about Jazz’s importance to the Mac, saying that it would open up brand new markets and Steve Jobs went even further in his enthusiasm, telling the attendees that Jazz would be bought by half of all Macintosh owners. Lotus planned a major marketing blitz to drum up interest in Jazz, with a focus on selling it as the ultimate Macintosh program. Lotus also announced that Jazz would be released five months later, in March of 1985.

By December 1984, Klunder and the other Excel programmers had brought the Macintosh version of Excel to basically the same stage the MS-DOS version had been before development had been canceled. New features had also been added, including a way for users to design their own reports, a first for any spreadsheet application.

Additionally, Excel now had the ability to generate a print preview that accurately showed what a printout of the current screen would look like, basically WYSIWYG. This feature was originally added as a convenience feature for the programmer working on Excel’s print features, as he had gotten tired of having to go some distance away to the room where the printers were11 every time he needed to test his print code.

The Excel team was helped out by a bit of a mistake from Lotus president Mitch Kapor. At a trade show where a prototype of Jazz was being demonstrated, Blumenthal and Slade were present and not only took copious notes, but also quizzed Kapor on various aspects of Jazz, such as how scrolling was handled and how spreadsheets were linked to graphs.

Kapor ignored his own programmers, who were deeply suspicious of these Microsoft employees snooping around, and generously answered a number of questions about how Jazz worked12. The Microsoft team then used this info to help refine Excel. At this point Microsoft had not announced Excel and apparently rumors about it were minimal to non-existent, so Kapor presumably was under the impression that the only spreadsheet Microsoft had was Multiplan, which was absolutely no threat to 1-2-3’s dominance.

In January 1985, as promised, Klunder recorded a twenty hour long videotape series explaining how Excel worked and was programmed, and where he had left off, then took off, fully intending to never return to Microsoft. According to him, his state of mind was “I’m totally burned out. I think technology sucks. I get rid of everything I own except what I carry around in a backpack. Go down to California and find work there as a migrant farmer.13”

Now without Excel’s lead programmer, Gates hired former Wang developer Philip Florence to head the Excel project, which continued to be solely focused on the Macintosh. Gates maintained a very close watch on Excel, and immediately ratcheted up the pressure on Florence to the same level Klunder had experienced, with Florence describing the experience as “a pressure cooker.”

The stress on Florence would only ratchet up even higher, and unlike Klunder he never took a six week vacation to pick lettuce and relax. Matters were also not helped along by the fact that videotapes Klunder had recorded had apparently been lost and were never found.14

Initially assuming that he was only managing the Excel project, Florence was shocked to get an order directly from Gates to start coding Excel directly, as well as do bug checking. The project, already behind schedule, began to fall behind even more. An exhausted Florence had a stormy meeting with Gates where he bluntly declared that it was not possible for him to wear the dual hat of project manager and programmer simultaneously.

Gates responded to this with his usual restraint. Which is to say that he started screaming at Florence and slamming his fist onto the conference room table. It wasn’t too long after this meeting that the overworked Florence suffered the consequences of 100 hour work weeks, plus all of the stress associated with working under Gates and had a heart attack that required him to undergo bypass surgery. That was the end of Florence’s involvement with Excel, and according to one source, he had made little progress in spite of his hard work and dedication15.

Fortunately for Excel, after six weeks of picking lettuce and living the simple life…Klunder’s backpack had been stolen and he was flat broke. In his words, he then said “Gee, I bet I know where I can get money fast. I can go back to Microsoft.16”

Microsoft paid for his bus ticket to head back to Redmond and Klunder went back to work on Excel, picking up where he left off, getting the other programmers up to speed and improving significant features such as the intelligent recalculation17 that would be a key differentiation from the Lotus 1-2-3. In the end, Klunder was responsible for around half of Excel’s entire codebase, and if anyone could call Excel their baby, it was him.

In January of 1985, probably after Klunder had taken off, Excel had been shown to Steve Jobs for the very first time. And he was not impressed with its stand alone nature, stating “You guys are crazy! Jazz will be the Macintosh program. It will be on the desk of every Mac!18”

Jobs felt that Excel needed to be an integrated program, maybe not to the same extent as Jazz, but with at least a word processing program. He also took issue with Excel’s support for macros, saying that Macintosh users would have no interest in using them. Gates stuck to his guns however, telling Jobs that Excel was a powerful program aimed at advanced users.

March came and went and Jazz was nowhere to be seen, with Lotus announcing that Jazz needed a couple more months of work. This was the first time Lotus had ever missed a release date, and it was a problem not only for Lotus, but also for Apple. The problem was that the Macintosh was really struggling by mid 1985, as its high price and lack of a true “killer app” were working together to keep sales far below expectations.

Apple had been counting heavily on Jazz to be the badly needed killer app that would get people off the sidelines, especially businesses and start driving major market adoption. The aging Apple II, now eight years old in 1985, was still accounting for a whopping 75 percent of Apple’s revenue, the Lisa was a massive failure, the Apple III had been a colossal failure, and now the Macintosh was looking mighty shaky. However a single killer app can make-or-break a platform and if Jazz couldn’t deliver, maybe Excel could.

After all, the original spreadsheet, VisiCalc, had been the catalyst for the Apple II to take off a few years earlier, so an even fancier spreadsheet, plus everything else Jazz brought to the table, should be just what the Macintosh needed. This made Jobs look far more favorably at Excel, since by this point he was getting desperate to get the Macintosh moving and was in fact only a month away from his resignation from Apple, after losing a battle with Apple’s board.

As Excel approached its official unveiling, rumors began to float around the industry that Microsoft was getting close to releasing a new spreadsheet for the Macintosh. However all queries to Microsoft about this received an official denial. The cat was pretty well out of the bag however, when invitations went out for journalists to attend a Microsoft press conference where Steve Jobs would be involved in some capacity.

Thanks to this and other rumors, Lotus and Mitch Kapor were able to confirm Excel’s existence a few days prior to its announcement, but Kapor remained calm when asked if he was concerned about this unexpected competitor. His position was that Excel wasn’t really a competitor to Jazz since Excel was only a spreadsheet and lacked the integrated programs (database, word processor, etc) that Jazz had.

Excel was officially announced to the world on May 2, 1985 in New York City. The launch event was planned to be held in the Tavern on the Green near Central Park, and Gates and the Microsoft team were booked into the Pierre, a luxurious nearby hotel. However when Gates arrived in NYC, he was angry at the cost of the Pierre and demanded that cheaper accommodations be found.

None could be located however, probably due to the need to be near to the launch venue, and thus a fuming Gates immediately went to the Tavern on the Green and began working with his programmers to set up the demonstration that would show the assembled guests Excel and its friendly Mac interface.

Unfortunately the demo was not working. The demo, scripted out by Jabe Blumenthal and Mike Slade, involved them actually working in Excel, with a large screen showing Excel and Gates commenting on what was going on. Although it had functioned perfectly back at Microsoft, here it was crashing the Macintosh as soon as it was launched. Gates and his programmers started screaming at each other, always a productive thing to do.

After hours of work Blumenthal figured out a new workable sequence that avoided any landmines in the still buggy build they were using, or so he hoped. Once Excel was able to be launched twice without crashing the Macintosh, Gates and his weary programmers decided to just cross their fingers and hope for the best.

The next morning Gates was a mess, having neither slept, shaved, or showered and according to one source19, he stank and had not bothered to put on any deodorant. In the words of one of the Microsoft senior managers that were there, “It was obvious Bill had not bathed in some time. I just couldn’t believe it. This was the most important announcement that we’d ever made. And Steve Jobs was there to endorse the product, as well as a lot of other important people. We’d really pulled out all the stops with the press, and here Bill was…I just couldn’t imagine, you know, it only takes five minutes to shower.20”

Fortunately the demonstration worked flawlessly and Steve Jobs' speech also went well, with him endorsing Excel as “the fastest, largest, and most full-function spreadsheet available in the world.21” This was a bit of a reversal from his previous endorsement of Jazz, and it went even further, with Jobs stating that Excel was superior to an integrated program like Jazz, even though Jobs was very careful to avoid saying the name.

Noting this, a journalist asked Jobs directly if Apple still supported Jazz, to which Jobs responded ”There is a market for an integrated package with a certain amount of power22” as Gates gave a faint smile.

As the press conference drew to a close, one journalist finally asked a question that everybody had been thinking…would Excel be coming to the PC? Gates knew he had to answer this question carefully, as Apple’s endorsement would be difficult to get if he promised a DOS version of Excel.

Therefore he diffidently stated “This is an issue of leadership. Apple has taken the leadership in this technology. Eventually, however, all technology becomes available to all people,23” a statement subtly promising a version of Excel for the PC market, once some type of graphical user interface for it emerged (such as…the as-yet-unreleased Windows perhaps). Jobs responded to Gates by saying “Yeah, and someday we’ll all be dead!”, to which Gates (after waiting for the laughter to die down) mischievously smirked and said “Not IBM!”

It must be said however that in the May 27, 1985 edition of Infoworld, as part of an article entitled Microsoft Strikes First in War Against Lotus, Bill Gates is cited as explicitly saying that Excel would eventually be ported to Windows24 and by extension, to the entire range of PC compatibles. Perhaps he gave an additional interview that went mostly unnoticed by Apple and Steve Jobs…keeping in mind that Jobs was highly distracted by the power struggle he was in at this time, which he would eventually lose to John Sculley.

Strong support for the Macintosh may sound odd coming from Microsoft, but no more odd than Steve Jobs endorsing a Microsoft product. At this point in 1985 Microsoft was still struggling just to get Windows to market and although MS-DOS was obviously very important to the company, they still viewed applications as their main bread and butter.

For example, in 1983 Gates stated that “during 1984, Microsoft expects to get half its revenues from Macintosh software.25” Granted he said this at a gathering of nascent Macintosh developers that was chaired by Steve Jobs himself, and thus was probably playing to the crowd at least to a certain degree. However there was a large amount of truth in what he said as Microsoft was first and foremost an applications company and would remain so for a few more years.

The press conference had gone well and coverage was encouraging, with one publication stating that Excel had the potential to “save Apple Computer from financial ruin by turning the Macintosh into a viable business computer.26”

At the Spring Comdex a few days later, Excel was shown off to the attendees and more journalists, where it garnered quite a bit of attention and interest…the problem was that Excel wasn’t scheduled for release until September, and Microsoft’s record with keeping release dates was…mixed, with the long gestating Windows project and its many missed release dates already causing it to be the butt of many jokes.

A few weeks after the Excel announcement and the Comdex show, on May 27, 1985, Lotus released Jazz. Reviews were…mixed. On its release day, InfoWorld had an article from reporter Tom Maremaa where he had asked Gates if Excel was targeted at Jazz or 1-2-3.

Gates responded “What is the most successful business program? 1-2-3. That is the state of the art in numbers solutions, and it is a very fine product. Now, the Mac plus Excel is the state-of-the-art numbers solution. We don’t believe in the Jazz philosophy that you take all your uses-words, numbers, database, and the resources of the machine-and spread them in five different directions. So there is significant compromise.27” Gates also had an ace up his sleeve to deal with Jazz’s integrated programs.

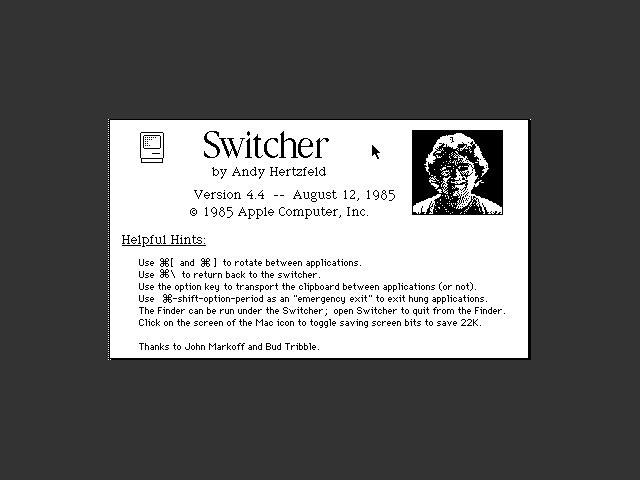

Ace Macintosh developer Andy Hertzfeld (and by “Macintosh developer” I mean he was Apple employee #435, built large sections of the Macintosh operating system, built most of the desktop accessories that shipped with the original Macintosh, and was one of the people whose signatures adorned the inside of the original Mac 128k) had developed a nifty application called “Switcher” that Microsoft had licensed and would bundle with Excel.

Switcher took advantage of the Mac 512k’s expanded RAM to allow the Macintosh to run up to four programs simultaneously, with the user “switching” between them. It was a very clever way to get around the Macintosh’s design as a single tasking operating system and it enabled Microsoft to claim that if you wanted integration, instead of being forced into Jazz’s five built-in programs, you could pick your own programs to “integrate” with Excel.

Hertzfeld had to do quite a bit of work to make Switcher work with Excel, and has an excellent article on the development of Switcher that I highly recommend reading if you want to know more.

In a rather startling break for Microsoft’s tradition, Excel was released on time, reaching the market on September 30, 1985. It garnered excellent reviews and even though it was Mac only, some reviews even said the combination of it plus a Mac 512k was a superior product28 to a PC running Lotus 1-2-3. Jeff Raikes, Microsoft’s director of application marketing said “...we gave the market a product that proved you could do more with a Mac than with an IBM PC.”

Infoworld’s Amanda Hixson, in an articled entitled “Excel: First Impressions” led off by saying “Despite its complexity, Excel, Microsoft’s new integrated Macintosh program, contains some of the best power features of any software product.”

She went on to praise Excel for its powerful macros and overall feature set, finishing by saying “Its almost impossible to understand why Lotus has taken so long to deliver Jazz while Microsoft has quietly been working on the product everyone thought Lotus would deliver. Whatever the reasons, Microsoft may just win this round in the game.29”

Microsoft went all in on grabbing control of the Macintosh spreadsheet market. Ads were placed not only in computer magazines, but also in mainline publications such as the Wall Street Journal. Starting in January 1986, Macintosh owners who had actually bought a copy of Multiplan, could get a special discount where Excel cost only 200 dollars instead of its regular price of 395 dollars.

When the Macintosh Plus was released that same month, it doubled the Mac 512k’s RAM all the way to a staggering 1 MB, which enabled Excel to create massive spreadsheets by the standards of the era, the Macintosh not having the same issues MS-DOS did with extended memory, expanded memory, conventional memory etc.

To the surprise of many, including Microsoft themselves, Excel caught fire from the start and quickly charged past Jazz in total sales. By December 1985, Excel was the top selling piece of Macintosh software, with a staggering 36 percent of the market. If you also count the sales of Multiplan (tagline “Hi! I’m still here somehow”) and Word, Microsoft actually took 50 percent of all Macintosh software sales for December.

Meanwhile Jazz only managed to account for 9 percent of the software market and that number was falling. Microsoft was also undoubtedly helped out by the fact that Excel cost only 395 dollars, whereas all the bundled applications inside of Jazz meant that Lotus charged 595 dollars initially, although in mid 1986 they did lower the price to match Excel’s pricing.

But it was too late, the Excel train was rolling at full steam and it was not only beating out Jazz handily, but Macintoshes loaded with Excel were also starting to show up in businesses, and even InfoWorld switched its staff over from PCs running 1-2-3 to Macintoshes with Excel, saying in the November 10, 1986 issue “After being loyal and dedicated 1-2-3 users for several years, we’ve just recently converted all out 1-2-3 files over to Excel. It’s that good.30”

At the end of 1986, Excel controlled 89 percent of the spreadsheet market on the Macintosh to Jazz’s 6 percent. In 1986 Microsoft had become the top software publisher for the Macintosh, with a combined market share across all applications of roughly half of all applications sold that year. This obviously didn’t threaten the massive install base of MS-DOS and PC compatibles, but it did provide a lifeline to the Macintosh, legitimizing it in the business world.

Excel would not be released for Windows until October of 1987, by which point it had benefited greatly from several years of maturity on the Macintosh, and was clearly a GUI based spreadsheet, not a DOS spreadsheet with a new coat of paint. Once released for Windows it rapidly began its climb towards total spreadsheet dominance, helped along by some very poor decisions by Lotus with 1-2-3.

But that’s a story for a different article.

https://www.wired.com/2009/08/dayintech-0806/

“Visicalc, We Hardly Knew Ye”, Infoworld, May 27 1985

Gates, Stephen Manes and Paul Andrews, 1994, Page 258

Gates, Stephen Manes and Paul Andrews, 1994, Page 259

The Making of Microsoft, Daniel Ichbiah and Susan Knepper, 1993, Page 157

Ibid

Ibid

The Making of Microsoft, Daniel Ichbiah and Susan Knepper, 1993, Page 160

Hard Drive: Bill Gates and the Making of the Microsoft Empire, James Wallace and Jim Erickson, 1992, Page 282

3rd Party Developers and Macintosh Development, https://www.folklore.org/StoryView.py?project=Macintosh&story=3rd_Party_Developers_and_Macintosh_Development.txt

The Making of Microsoft, Daniel Ichbiah and Susan Knepper, 1993, Page 159

The Making of Microsoft, Daniel Ichbiah and Susan Knepper, 1993, Page 158

Gates, Stephen Manes and Paul Andrews, 1994, Page 277

The Making of Microsoft, Daniel Ichbiah and Susan Knepper, 1993, Page 160

Ibid

Gates, Stephen Manes and Paul Andrews, 1994, Page 277

The Making of Microsoft, Daniel Ichbiah and Susan Knepper, 1993, Page 161

The Making of Microsoft, Daniel Ichbiah and Susan Knepper, 1993, Page 160

Hard Drive: Bill Gates and the Making of the Microsoft Empire, James Wallace and Jim Erickson, 1992, Page 286

Ibid

Gates, Stephen Manes and Paul Andrews, 1994, Page 278

The Making of Microsoft, Daniel Ichbiah and Susan Knepper, 1993, Page 164

Ibid

“Microsoft Strikes First in War Against Lotus“, InfoWorld, May 27 1985

When Computing Got Personal, Matt Nicholson, 2014, Page 141

Journal American, May 3, 1985, quoted in Making of Microsoft, Page 165

Bill Gates on Excel and MS Windows, InfoWorld, May 27, 1985

Hard Drive: Bill Gates and the Making of the Microsoft Empire, James Wallace and Jim Erickson, 1992, Page 287

Excel: First Impressions”, InfoWorld, May 27 1985

Journal American, May 3, 1985, quoted in Making of Microsoft, Page 169

Andy Hertzfeld, rhymes with “weld,” not hertzfield.